The First Law: when the story justifies the means (or four ways to narrate evil)

One of the great thematic concerns of Joe Abercrombie’s The First Law series is the nature of violence. How do we, as human beings, come to do what we have proven we do best: harm. What motivates us? What pushes us down the ravine of evil? What are the excuses we hold up under scrutiny? Beyond that, what are the justifications we whisper to ourselves before sleep?

For me, these questions are the beating heart of the novels, all nine of them. The question mark that wraps itself like a snake around the necks of the characters. I also think that these characters can be classified into four categories, and that these categories not only represent four different ways of seeing and existing in the world, but also indicate the degree and the particular way in which they behave like real assholes.

Although I am very suspicious of any literary essay based (solely) on taxonomy, I also can’t deny that while I was finishing The Age of Madness trilogy a sort of chart began to grow in my mind, one that I did not manage to uproot completely and ended up germinating into the core idea for this text, which I finished writing because I honestly believe it’s a great help when it comes to analyzing the very different (but tragically universal) ways in which the characters of The First Law justify to themselves (and to the unsuspecting reader) their descent (more or less precipitous) down the ravine of evil.

The categories are based on two things: 1) the characters’ perception of the world and of themselves, and 2) their attitude towards the world, the standpoint and disposition from which they act. These are the two pillars on which their internal narrative is built —a key factor, because when it comes to carrying out evil and the perpetration of violence, what pushes us over the edge are not our feelings and desires, but the stories we spin to imbricate these acts into a coherent system of meaning.

Certainly, desires and feelings don’t help. They drive us until the soles of our feet are on the very edge of the ravine, but that first step, the first slip, has as its catalyst something much less obvious, something that camouflages itself as logic and reason, for it’s our reasons that end up condemning us (Luque, 94). This, I hope, will become clearer as we go over the four categories.

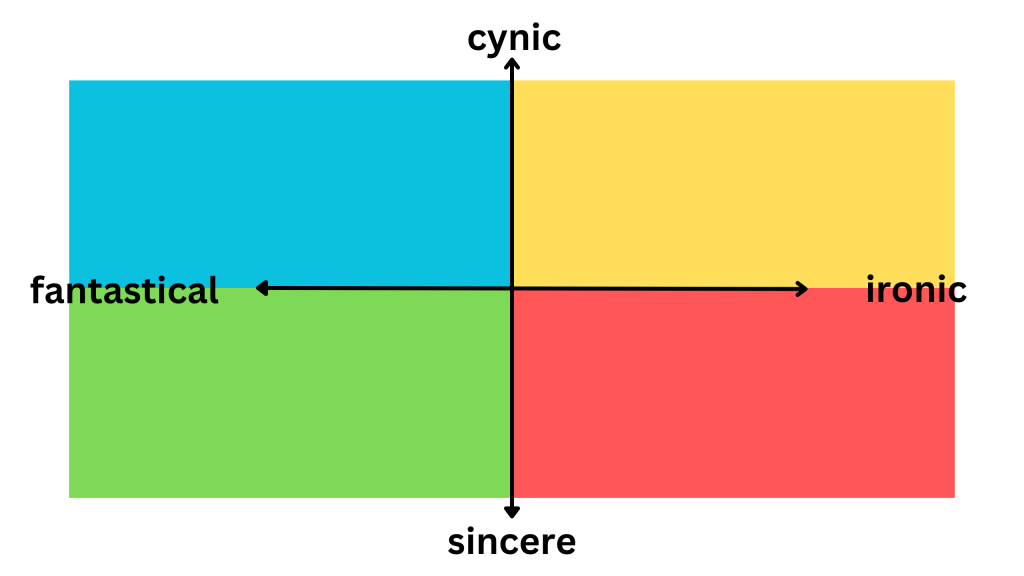

Which are the following: cynical, sincere, ironic and fantastical (I do not call it ‘fantastic’ because I refuse to fall into the tradition of equating the fantastic with words like ‘madness’ and ‘delusion’).

They are grouped like so:

Like this, one can have an ironic-cynical or fantastical-sincere inner narrative, but not a fantastical-ironic or a cynical-sincere one, because there is nothing that repels cynicism more than sincerity, and the fantastical does not resist irony (or any kind of self-relating humor, really). The x-axis indicates the perception of the world and of the self and its spectrum is that of reality. The y-axis indicates a character’s general attitude towards the world and its spectrum is that of vulnerability.

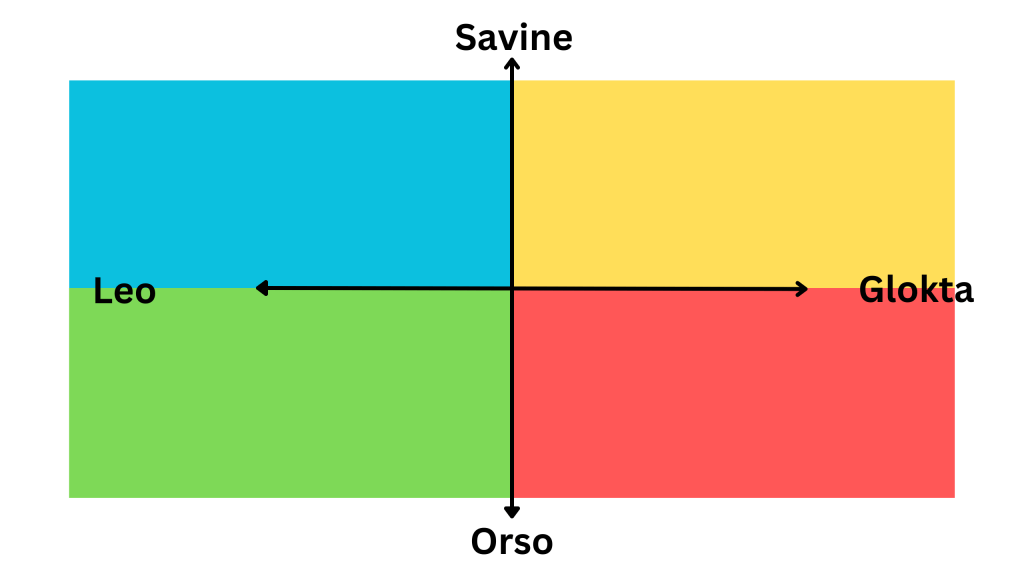

Because everything is always clearer with examples, I’ve chosen four characters that I feel encapsulate each cardinal point the best. Let’s start.

SPOILERS FOR THE ENTIRE SAGA (all 9 books) FROM HERE ON IN!

Sand dan Glokta: the ironic

Few characters manage to make readers laugh while pulling out other characters’ fingernails. Glokta’s dry humor achieves this and more, but it’s not that that makes his internal storytelling ironic as well. At least not just that.

I debated long and hard what to call this end of the spectrum. I toyed with other terms, like ‘realistic’ and the more general ‘humorous’, and I do think my use of ironic carries within it the connotations of both, but it is also greater than the sum of its parts. The ironic internal narrative is characterized by an unrelenting commitment to the truth of things, to seeing the world as it is and not as we think it should be (worse still, as how we want it to be). It is the postmodern type of irony that comes from the loss of faith in the Big Narratives, it is a disenchantment of the world, it is the reflexive reaction of laughter in the face of tragedy. It is humor because of realism.

Glokta represents this better than anyone. He suffers constantly under the heavy weight of knowing, personally and intimately, the workings of the world: its indifference, its manifest lack of justice, of meritocracy, of meaning. In the first trilogy, it is Glokta who eventually discovers the hidden puppet master pulling the threads of the Plot because he is the one who sees life as it is. His inner narrative is devoid of any manicheism, any self-deception.

Now, ironic internal narration is neither neutral nor easy to maintain. It is neither the default nor the standard. Glokta constantly has to remind himself how the world works, what reality is like. Body found floating by the docks… It is not only a reminder of the very real danger he faces everyday, but also a litany, a commitment to disenchantment. It is a total abandonment of the imagination: the thinking of other worlds, of other selves. An ironic narration, in its most extreme aspect, is radical realism: this is the way things are, the way they have alway been, the way they always will be.

When you see the world like this, humor becomes fundamental. It’s the only valve the ironic narrator has that can relieve some of the pressure of living under the weight of radical realism. A way to laugh in order not to cry. Glokta’s acid and sarcastic humor is a necessary reaction to seeing the world only (!) for what it is.

Leo dan Brock: the fantastical

Leo dan Brock is the king of deception. If Glokta observes the world with clear and watery eyes, Leo walks through it with a sack over his head and, I’m sure, with his eyes tightly shut as well. He suffers from total blindness when it comes to recognizing his own faults and limitations, to call him arrogant is an understatement, and he shows zero understating of the political, social and economic workings of the world he lives in.

If ironic inner narration lacks imagination, then the fantastical is characterized by a type of imagination that is completely removed from any factual or empirical foundation. It is Leo, telling himself and anyone who will listen that he is a great general when his mother is the one responsible for his victories. It is Leo, believing he managed to forge an alliance with his mortal enemy when it was in fact his wife who made it happen. It is Leo, unable to acknowledge the attraction he feels for his best friend because it just doesn’t fit his self-image. It is his commitment, absolute and unhealthy, to the idea, the image, the fantasy of the Young Lion.

Fantastical inner narration is self-deception. It is willful blindness and a total lack of self-reflection. In its most radical form, it is insanity: living and acting according to an unreal framework, following parameters that do not coincide with factual reality. It is, in the simplest of terms, acting like the Young Lion when you are no more (and no less) than just Leo.

And the fantastical narrative goes even further, because it imposes its version of reality above all others. A person who narrates their life fantastically is not content doing it alone. They try to transform reality, to actualise their fantasies. It’s Leo, precipitating a civil war only so he can become the savior he already believes himself to be.

The fantastical narrative, moreover, is immune to all logic, for it admits neither argument nor proof that could weaken its narrative pillars. It cannot. One of Leo’s most reprehensible characteristics, which also marks him as one of (if not the most) fantastical characters of the entire series, is his inability to listen to the advice of his mother or his more sensible friends. People who narrate their lives fantastically cannot be appealed to with logic, only through manipulation. This is why it’s Savine, Heugen and eventually Jurand who end up ‘managing’ him. They don’t do it through logical arguments, like his mother tried to do, they speak directly to his fantasy: Leo, the savior of the people. Leo, the just and noble knight.

What happens, then, when the fantastical narrator is confronted with reality? There are two options: Either they close their eyes tight and cut the disruptive element out of their life, like Leo did with Jurand after Sipani, or they are forced to reevaluate their perception of the world and of themselves, like Jezal did, after a sledgehammer hit him in the face (long live symbolism!).

This is why humor is the fantastical narrator’s natural enemy. As Orso rightly states, Leo suffers from an unforgivable lack of a sense of humor. And this condemns him. The ability to laugh at yourself is key to self-reflection. A narrative like Leo’s, where he is always right and always does the right thing, crumbles the moment it’s subjected to a minimum of sarcasm. Irony unmasks, and there is nothing more anathema to the fantastical than a direct confrontation with reality.

Orso dan Luthar: the sincere

Orso, on the other hand, does know how to laugh at himself. Usually in a rather self-deprecating way. This already puts him firmly in the ironic category, but Orso, more than anything else, represents for me a particular attitude towards the world.

There is something almost tender about Orso, something that invites affection and admiration, despite him being an almost thirty-something who has never done anything with his privileged life. And it’s not just the readers who feel that pull, as evidenced by the plethora of comments along the lines of ‘I’d never thought I’d like this character so much’. The characters themselves seem to gravitate towards him. Orso, unlike the majority of The First Law characters, enjoys a rare amount of loyalty. We are all, I think, a little like Savine; drawn to his, um… his something.

And well, what is that something? I think part of it is his sincerity. He almost always acts from an honest desire to participate in the world, to be involved. Something quite rare in the Circle of the World, because what characterizes the sincere attitude is the level of vulnerability to which the sincere person is exposed to. Because sincerity always entails involvement, it necessarily implies putting oneself in the hands of others. It also means recognizing this not only as a fundamental feature of human life, but as the very meaning it. And that’s dangerous.

Orso does this over and over again. He is vulnerable with Savine, whom he never stops loving even though it hurts him. He is vulnerable with Hildi, though he knows she can be taken from his side at any moment. He is vulnerable when he trusts Tunny, and he feels the pain of his betrayal when he believes it to be true. This type of sincerity is attractive, especially in a world where the other option always seems, and often is, the more sensible one. This is, I think, a big part of what that earns Orso the loyalty and admiration of both characters and readers alike.

Savine dan Glokta: the cynic

On the other side of the spectrum we have Savine. She represents better than anyone the opposite attitude towards the world: cynicism. It encapsulates the belief that human beings are no better than animals, motivated solely by self-interest and the need to satisfy their most basic desires: security, power, pleasure. From that belief is born the corresponding attitude: the hermetic withdrawal from any honest involvement with the world and its inhabitants.

The cynical attitude is characterized by a total rejection of the idea of interaction. It is a defense mechanism that avoids positioning the cynical narrator in any vulnerable situation. In Savine, it manifests itself as the transformation of her interpersonal relationships into interpersonal transactions. Savine always acts from a position of distance. She treats others as a means, never as an end. She does not see human beings. She sees numbers, statistics, money.

There is no scene more illustrative of this attitude than her reaction upon discovering the children working in her Valbeck factory. She immediately dehumanizes them, turns them into numbers and imbricates them into a business framework in order to interact with them from the safety of distance and the coldness of the language of economy. This is how she tries to escape the horror that would mean engaging with them in a sincere way.

The cynical attitude makes it impossible to create honest bonds with other individuals, and also closes the possibility of getting involved with the shared world. It isolates the cynical narrator from any community, from any future project that has as its north the betterment of the majority, because it sees compromise as dangerous, and involvement as fatal.

The Circle of the World

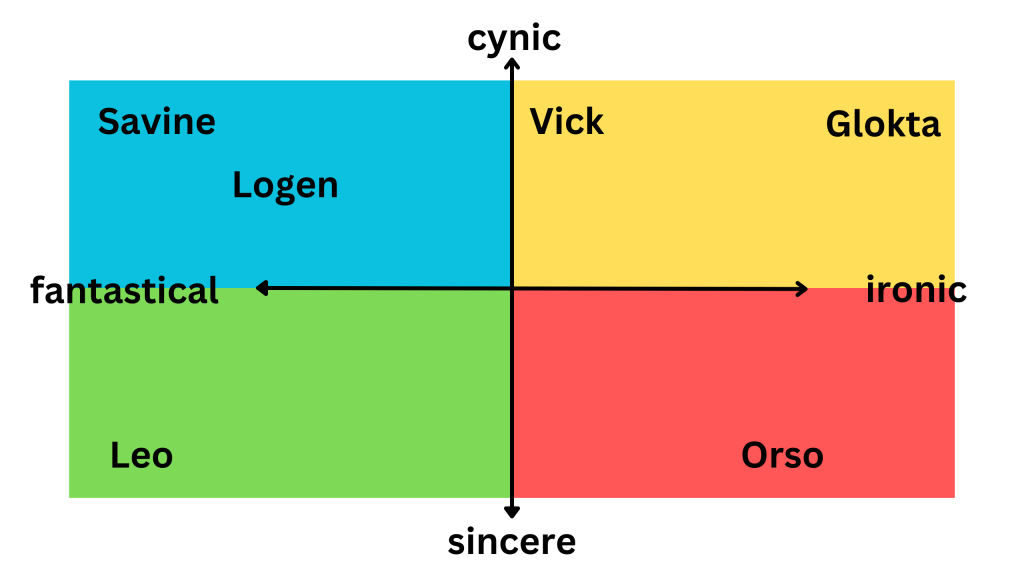

Having (hopefully) clarified what I mean by these four categories, our chart now looks something like this:

But reality (as always) is more complicated. Although I have used these characters to illustrate the fundamental characteristics of the chart of evil’s cardinal points, it actually looks more like this:

(With some additions).

The axes cannot be divorced. Everyone has to have two coordinates because the way the characters perceive the world and themselves directly influences the attitude with which they move and act in it. In the same way, the consequences of their actions either corroborate or disprove their vision of the world and of themselves, influencing, in turn, these perceptions.

So, Leo is fantastical and sincere, because despite living with his head stuck in fantasyland his actions are still motivated by a sincere desire to participate, to get involved, and he does forge bonds with others and with the world in general, though they are certainly colored by his fantasy. His fantastical narrative makes him believe he is invincible, for example, and so he is not prepared to face the death of his friends, and he gets involved with a project only insofar as he is allowed to be the leader, the savior.

Savine is fantastical and cynical. Her fantasy is based on the image she has of herself as an entirely rational business woman capable of doing whatever it takes to get ahead. Her fantasy feeds into her cynicism, and so the capitalist framework through which she perceives all her interactions with other people and the world takes root deep in her pysche.

Glokta is ironic and cynical. In his case, the recognition of the cruelty of reality moves him to completely seclude himself and reject any sincere involvement with the world, away from honest human relationships and from trying to find any meaning in life beyond survival.

Orso is ironic and sincere. He has the ability to see things as they are without letting himself fall (completely) into a pit of despair. The lifeline that makes this possible is the recognition of the need for vulnerability in order to live a life worth living.

Plot twists

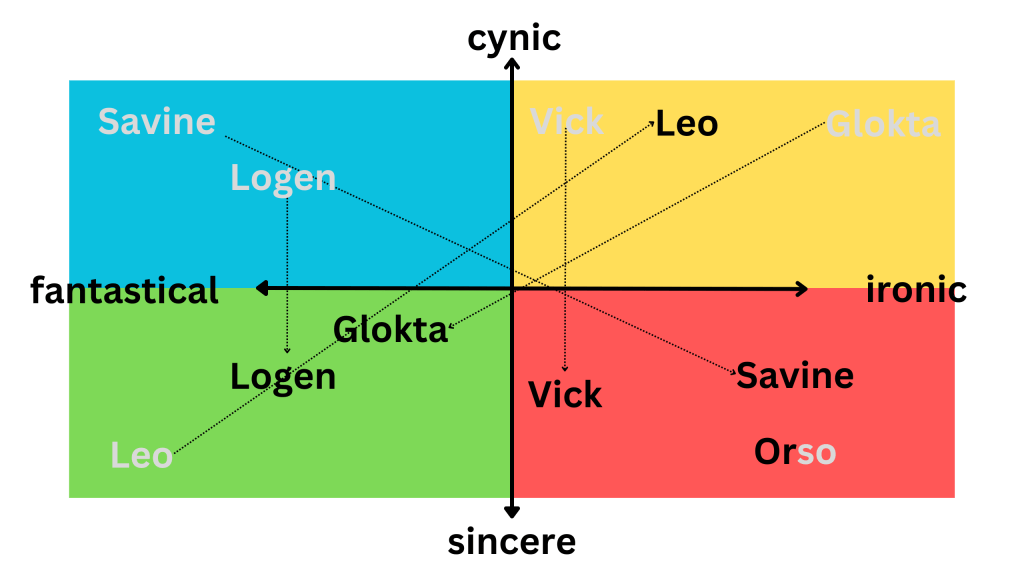

Now, these narratives are not static. They change, they evolve, and I think you can plot the development of the characters by following their trajectory across the chart of evil. A more dynamic depiction would look something like this:

(The names in gray indicate their original position and the ones in black the end of their trajectory).

By the end of the saga, for example, Glokta’s view of himself becomes much more fantastical. In his final confrontation with Savine, he tells her that everything he has done was to save the Union from Bayaz. And it is Savine, who has left the fantastical behind, forced to change by her experiences in Valbeck (which showed her how vulnerable she was) and motherhood (which stripped her of any pretense of distance from others), who forces him to face the truth: Glokta wants to become Bayaz. The fact that Glokta denies it, that he is unable to see the truth of her arguments, is what signals to me that Glokta has fallen into fantastical storytelling. (I’m not saying wanting to become Bayaz is his only motivation, more often than not we do things for a variety of different reasons, but the fact that he completely denies it says enough about what and how he thinks of himself).

Leo’s and Savine’s cases are also significant. The two of them end up in diametrically opposed quadrants, respectively. Leo goes from having a fantastical narrative to adopting a far more ironic worldview. Reality bursts so violently into his fantasy that it is impossible to move on without recalibrating his understanding of himself and the world. He also leaves behind all attempts at sincerity, taking up the shield of cynicism to protect himself from the pain of the loss of his friends, his body and of the story that had previously given his life meaning. I think there is no better proof of this change than the total disdain he seems to feel for his children. Leo completely refuses to get involved with them. He has to protect himself at all costs, and to care about others, even his children, is to expose himself.

Savine, by the end of the saga now firmly in the realm of irony, finds a way to become more sincere in her actions. She feels an urgent need for meaning, for there to be a Point. This can’t have been for nothing. And while clearly her need for safety and protection are still a primary motivation (which is why she is not right next to Orso) she is more open to forming relationships that make her vulnerable.

Two other examples that I think are important to mention are Logen and Vick. Both have a similar evolution. They move from a cynical attitude that avoids all vulnerability to a much more sincere one that opens them up to the possibility of forging meaningful bonds with others. The key difference is that Logen never becomes honest with himself. He never manages to discard the fantasy that he is better than he really is. He never manages to tell Shy about his past, for example, because this would mean a total disruption of the story he tells himself.

Similarly (but also fundamentally different), Vick begins the trilogy distrusting everyone and keeping them at a safe distance. She then begins to forge a bond with Tallow, however reluctantly, and the development of their relationship signifies Vick’s move from cynicism to sincerity, and therefore vulnerability. At the end of the saga, Vicks makes the decision to leave the Union behind to go in search of a new beginning. This is, in my opinion, admirable. With Tallow’s betrayal fresh in her mind, she is still able to recognize her desire to be loyal to people, and though the last time she did so ended up in betrayal and pain, she is willing to try again. The rejection of Glokta’s offer marks the difference between the two of them: both ironic, but one willing to weather the terrible contingencies of vulnerability, the other not so much.

Orso is one of the few cases where I think there is no trajectory, or at any rate very little. His character arc relies much more on acquiring new skills, like confidence, but I personally think his worldview doesn’t change that much. Nor does his attitude. Oros dies as he lived: laughing at the world, at himself, more importantly laughing at Leo and, most importantly, doing so wholeheartedly.

Going down story by story

And what, then, does all this have to do with evil?

At the beginning, I said that the descent into the ravine of evil does not occur because you feel certain feelings or desire certain things. Generally, these things have to be channeled first. They have to be justified. Most people have, after all, some sort of moral compass, and if they’ve happened to misplace theirs the threat of public shaming is often enough to curb our most immoral tendencies. It’s in the space between desire and justification where narrative becomes fundamental. Where narrative becomes.

Leo does not want to be king. The Young Lion knows that he is the only one capable of saving the people of his country from the terrible corruption of the government. Save is not a bad person, she is an intelligent, capable and entirely rational business woman doing what everyone else is doing, only better. Glokta is a torturer, sure, but the world is unfair and cruel, it is not logical that he has become unfair and cruel too? Orso is doing the best he can, but in the Circle of the World your best is often just not good enough.

The First Law and its characters are an inquiry into the main tool we use to justify our evil and our violence to ourselves and to others. We as readers are watching, observing as voyeurs through the window that Abercrombie’s prose opens up for us, the machinery with which these characters rationalize their crimes, their failures. From desire to action there is no single moment. There is a story, told and heard in less than a second (Luque, 93-94).

What is so fascinating to me about Abercrombie’s novels is that he develops these inner narrations in tragic and terrible slowness, letting us see exactly how the characters justify their tragic and terrible actions to themselves. The detail that first sparked this thought came to me suddenly while reading The Age of Madness. I noticed that the phrase ‘he told himself/she told herself’ appears surprisingly little, considering the novels’ narrative voice. And when the phrase appeared it seemed to be in key moments. And when I noticed this lack, I just couldn’t unsee it.

Abercrombie erases from his characters’ internal narration any sign of his own narration. The degree of identification we as readers have with the characters’ thoughts is immense, the distance is almost negligible. It’s never ‘Leo thought to himself…’ because that would mean making the machinery explicit. To render obvious what works only in the dark. Abercrombie’s technique is clean, detailed, meticulous. His style is brutal, intimate, raw. Together they create a narrative of evil that is, oh God, understandable. It is coherent. It is rational. It makes, oh no, it makes sense.

Because the actions of the characters are more than reprehensible. They are, of course we know, immoral. We know that what they are doing is wrong. But well, their world is very cruel. And they have no choice. They are, you could even say, forced to act that way. Didn’t you read the book? It’s not their fault this is the world they live in.

See how insidious narrative is? How subtle its transformation of excuses into reasons, of justifications into logic?

Pure alchemy. Real magic.

Good news and bad news

We all feel like hitting someone from time to time. We all want to feel safe, protected. We all want things that, if vocalized by someone else, we’d pretend disgust us. We all wonder what we’d be willing to do, how far we’d be willing to go, to get that which lies latent in our personal definition of the word ‘desire’. But, and this is the good news, what differentiates the bad guys from the good guys are their actions. Having ‘bad’ feelings does not make you a bad person. Acting badly makes you a bad person (Luque, 93).

Bad news: what makes the bad guys be able to do bad things is their ability to rationalize evil. And this process of rationalization is nothing more (and nothing less!) than the spinning of a story. It is the creation of a narrative, and here comes the worst news of all, we all tell stories.

We do it everyday. We do it all day. Internally and externally. We do it because we don’t know how not to do it. But more good (?) news: not all of us are as good storytellers as Leo, as Savine, as Abercrombie. This means that, hopefully, we’re not all assholes like them either. Thank God we don’t have the sweeping, relentless talent to weave our worst failings and our biggest immoralities into a coherent, cohesive inner narrative we can use to sleep peacefully at night. Congratulations!

The First Law is, of course, an exaggeration of these narrative processes of justification. And it should be taken as that, a stretching of reality to its limits. It is emphasis through caricature, and it is also true. The First Law is an examination of where the violence we do to ourselves and others comes from. And I think Abercrombie hits the nail on the head. By slowing down the internal machinery that actualices our violence to give us a glimpse of how its gears fit and turn, by bringing the context that turns the edges of the ravine slippery, he renders the characters’ actions immoral, yes, but acceptable (Luque, 101).

And if we can accept that, then what else are we capable of accepting?

tag urself i guess

If you’re anything like me, the question that pops up next is clear: how do I know the type of my own inner narration?

It’s very difficult to resist the temptation of assigning yourself one (more) label you can use to continue building the eternally tottering tower of your identity. Don’t worry, I’ve got you covered. In this case I even think knowing where you stand on the chart of evil can be helpful. In part because I believe some types of narration are more harmful than others, because I believe there are stories that make us more prone to evil insofar as they assimilate our possible actions more quietly and efficiently into a cohesive structure of meaning. Because they camouflage excuses and justifications as logic and reason with more skill and less friction. Because there are stories that withstand the onslaught of reality better than others. Because there are stories, in short, that are better stories than others.

So certainly my first piece of advice would be to avoid falling as much as possible on the extreme side of the fantastical. There is a reason why Leo is one of the most hated characters in the entire saga, a reason why we all applauded when Orso asked him how the leg was doing. There is nothing more unpleasant than a person who is hell-bent on living a lie, worst still when that lie has to do with how good of a person they are.

Beyond that, the fantastical narration is contagious, it never affects only the sick. So how can you find out if you have contracted the virus? Well, if in your internal monologue you are always simultaneously the hero and the victim, better get yourself checked out. Also be on the lookout for the first symptom: the inability to laugh at yourself.

I have also implied, not so subtly I think, that the other end of the reality spectrum, that of irony, is the best. And though I do not take it back, here are a few caveats: While I do believe that sincerity and irony can coexist, it’s a fine balance. The field of irony is not fertile ground for sincerity, because it camouflages its honesty in double meanings and black humor. Irony unmasks, but it always runs the danger of disenchanting as well, of totally rejecting healthy imagination and condemning itself only to the realm of the possible, of completely salting the ground where one should strive to cultivate a sincere attitude towards the world and towards others. After all, to be able to recognize the humanity of a stranger, one must be able to imagine them as human. And that’s where fantasy comes in.

Sincerity, as I do hope to have hinted at skillfully enough, is the only way to live a life worth living. Now, I understand the instinct for self-confinement, for quarantine, especially if one tends towards the side of irony. But that is not a viable solution. Life is something shared. And this means being involved in the world, with the world, with others, for others. It also implies being vulnerable (Garcés, 22). It implies the risk of being laughed at, of being disbelieved. The pain of loss, of doubt. It implies planting a garden only for someone or something to come by and set fire to it. It implies, always, the work of replanting it so you can sit for a while, in good company, to watch the flowers grow.

My final advice is this: Look for the right balance. The characters in The First Law are extremes because it is at the limits where fiction can interrogate more aptly and poignantly the workings of morality. Exaggeration is illustrative and it is fun (Luque, 75). But it is not very practical.

I don’t think it’s appropriate, healthy nor productive to narrate your life and your self only fantastically. But neither is it appropriate, healthy or productive to do so only ironically. Relentless commitment to realism is unsustainable, even if you try to alleviate it with humor. That’s like treating the symptom without eradicating the disease. A certain degree of the fantastical, or rather of fantasy, is necessary. It is essential to nurture fantasy, a term I use here to denote a type of imagination that has its head in the clouds but its feet on the ground, not only because it is the fertile ground from which empathy is born, but also because it is the realm of difference. Of otherness. And every attempt at improvement, whether personal, communal, moral or not, has always started from the question is there not another way?

And, although it pains me to admit it, you cannot go walking around with your heart in your hands. Something I wish someone would’ve told Orso: To protect others, you have to protect yourself. Rather than walls, however, I recommend another type of defensive architecture: the watchtower. Let your cynicism be a watchtower, a vantage point that discovers and alerts, rather than a wall that distances and isolates.

So perhaps I was right to be suspicious of any essay (mine especially) that relies on taxonomy and its bold lines. But like Abercrombie’s characters, the chart of evil is an illustrative exaggeration. I hope it helps, hope it makes sense. If it’s not too much to ask, I hope it leaves you with a new vocabulary, another way to think and talk about things. If that is too much to ask for, well. Thank you for reading anyways.

References

Las cosas como son y otras fantasías – Pau Luque

Un mundo común – Marina Garcés

Leave a reply to traspapelada Cancel reply